Cheryl Dumesnil

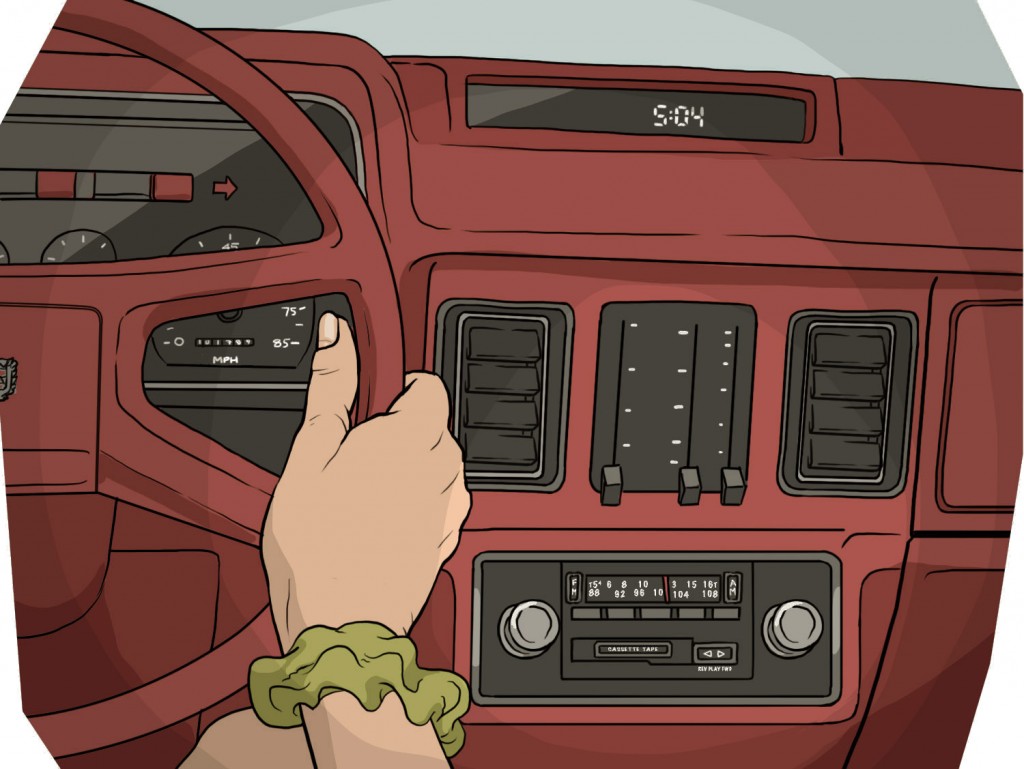

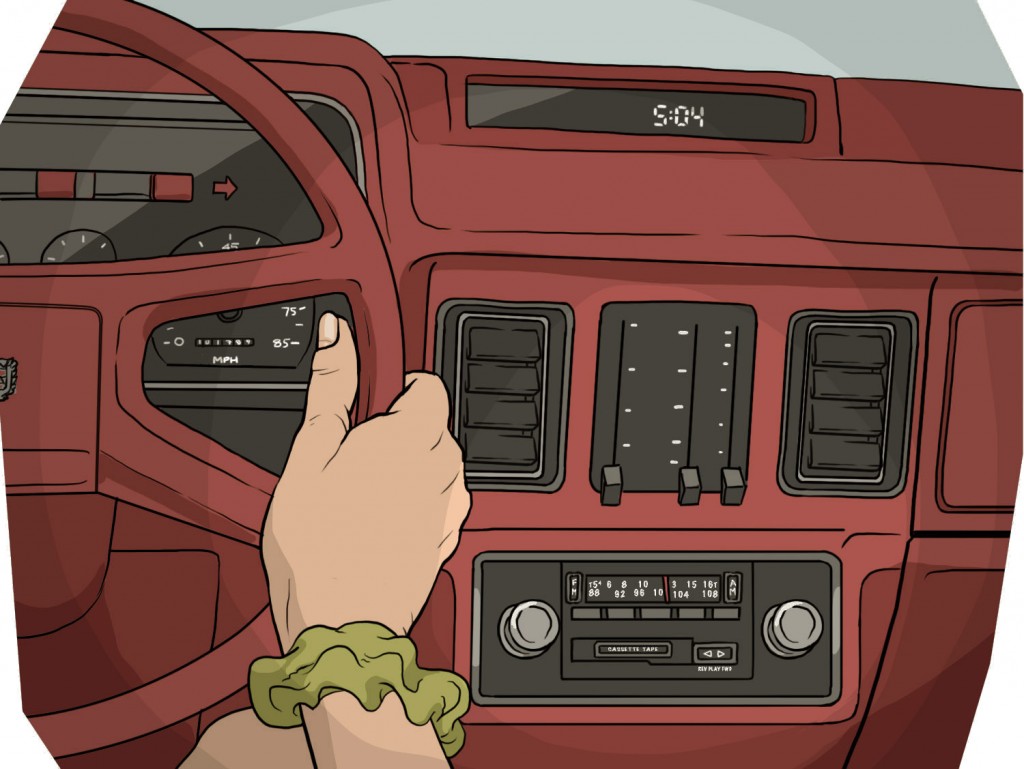

I was driving my beat-up Mercury Lynx from my job at Muller Construction Supply to Bellarmine College Preparatory, the high school where my brother went to school and where my boyfriend was the set designer for the theater. Tom Tom Club’s “Genius of Love” was playing on the radio when my car started chugging. “Damn it, what’s wrong with my car now?” I thought. “Flat tire?” Then the radio cut out. “Something’s really wrong with my car,” I thought. Then I saw people running out of the bodega on the corner. “Something’s really wrong with my car,” I thought. “So bad people are running out to look at it?” Then I noticed the stoplight in front me, bouncing on its pole. “Earthquake,” I thought, relieved that I wasn’t staring another huge car repair bill in the face.

I’d lived in California all my life. As far as I was concerned, “The Big One” was an earthquake myth—a thing we talked about that probably wouldn’t ever happen. I came to understand the gravity of the ’89 earthquake in slow stages.

When I arrived at the high school, all the theater geeks—including my brother and boyfriend—were standing outside. The building had been evacuated. Someone said the Bay Bridge had collapsed, and one of the boys started crying—his father commuted on the Bay Bridge.

We had a limited ability to make phone calls, but somehow I convinced someone to let me in the cinderblock theater so I could call my mom. I told her, “I think I’ll just go out to dinner and drive home later, when there’s less traffic.” “You will NOT,” she said. “You will come home right now.” Had I experienced the earthquake in a building instead of in a car—where I was insulated from the noise, where the tires absorbed much of the shock—I might have understood the tone in Mom’s voice. Instead, I was pissed that I couldn’t go out to dinner with my boyfriend. I begrudgingly packed my brother in my car and headed home. It took two and a half hours to drive fifteen miles.

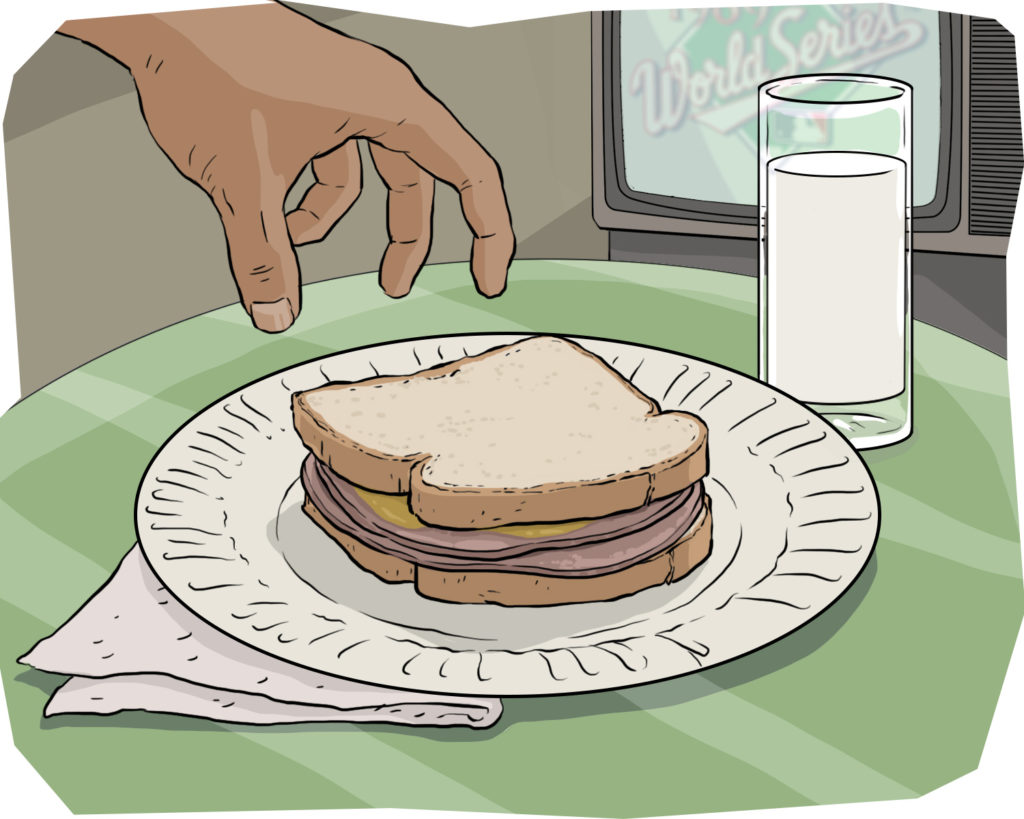

Later that night, after watching images of earthquake damage on the television, I called my boyfriend, also a long-time Californian. We talked about how weird it all was, how our understandings about earthquakes had changed, how we used to think earthquakes were cool, but how suddenly even a little aftershock seemed scary. “Here comes another one,” he said. It took a couple seconds for the trembling to travel the 15 miles between us. “Oh yeah,” I said. “I felt that, too.”

That change has been permanent. Even twenty-five years later, when I feel an earthquake start rumbling, instead of thinking, as I had throughout my childhood, “Oh cool! An earthquake!” I wonder, “How long will this last? How bad is it going to get?”