Randel K. Chow

I was working at Apple Computer in a building called De Anza 3, part of what was then Apple’s Cupertino campus (years before the Infinite Loop complex was built). I was getting ready to leave work to head to the guitar shop to meet my coworker, who had already gotten on the road.

At first, my colleagues and I thought the shaking was just one of those occasional moderate quakes. But this time, the tremor persisted, intensifying while all the lights and power went out and debris started falling from the ceiling. I ducked under the table in my cubicle, fearing the whole ceiling might collapse right on top of me. As I cowered under the table in the dark, the violent shaking continued for what felt like an eternity, although in reality it could not have been more than ten seconds.

As soon as the quake subsided, the frightening rumbling gave way to an eerie silence, one that was hard to ignore because of its stark contrast to the usual drone of computer fans to which we had grown accustomed. My colleagues and I emerged from our shelters and beheld shattered windows and a floor littered with ceiling fallout. We hastily made our way down the stairs from the second floor. I noticed that the stair railing had partially disconnected from the wall. We evacuated to the parking lot. Some folks turned on their car radios to listen to news broadcasts. We heard terrifying reports of collapsed freeways and raging fires from gas main explosions.

Meanwhile cars jammed De Anza Boulevard. The radio announced horrific gridlock on the freeways, so most of us felt it was more prudent to stay put I grew restless after an hour or so of waiting it out, and so I got into my car to brave the side streets (the radio traffic reports had warned that I-280 was nearly impassable). It was a most surreal experience, inching hopelessly among bumper-to-bumper traffic through the pitch black night as all street lamps were disabled by the mass power outage, the only illumination coming from the headlights of the endless parade of cars trapped in the snarl. After a frustrating ninety-minute journey from Cupertino to Willow Glen, I finally made it home.

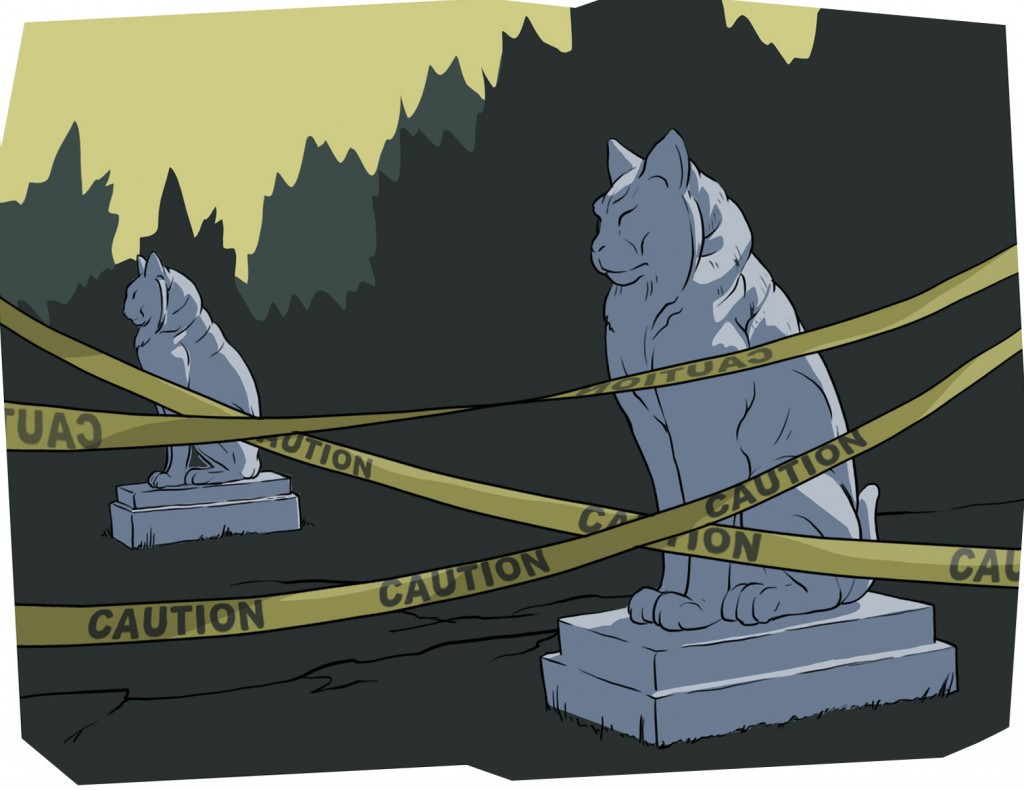

Our management instructed us to stay home for the next two days. After that, each of us were allowed to enter the crippled building for only a few minutes, long enough to retrieve our belongings.

De Anza 3, the only Apple building damaged by the quake, was left uninhabitable with structural as well as water damage: this occurred on the fourth floor after the ceiling sprinklers were sheared by the violently shifting ceiling. The inhabitants of that building were relocated to various other Apple locations; De Anza 3 underwent repairs, and was out of commission for a year.