Patricia Wakida

Its 1989 and I’ve landed a job with an Asian American newscaster, Wendy Tokuda, and a Jewish American television producer, Richard Hall, who is Wendy’s husband. As their babysitter. They have two splendid hapa daughters— Maggie, a gleeful five year old, and Mikka, an eight year old bookworm who splits her after-school extracurricular time between piano lessons and Hebrew school, and tonight she is dedicated to her studies of the Aleph-Bet. It is also a night that has been dubbed the “Battle of the Bay,” an epic World Series showdown between the Oakland A’s and the San Francisco Giants, and reports off the streets of the obscene levels of public swaggering and chest puffing in anticipation of Game 3 are off the charts.

I arrive at the family’s home in the late afternoon to take Mikka to Hebrew school and then begin preparing dinner with Maggie within my sights, at the kitchen table. I have been warned that their Mom won’t be home until late tonight due to the game since, yes readers, she’s one of the live reporters broadcasting from Candlestick, and boy it’s gonna be a doozy.

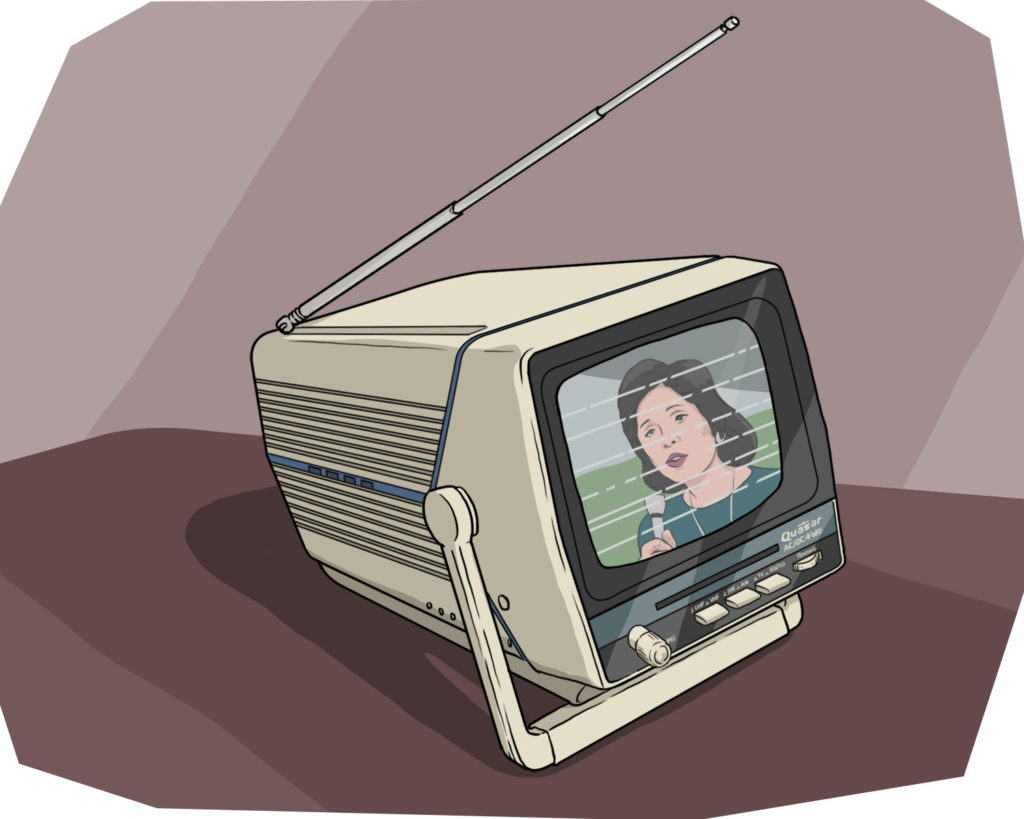

Despite the fact that both parents work in television, the two girls are curiously uninterested in TV, so it’s a rare night that I switch on the portable kitchen set that night, its tiny screen no larger than a slice of bread, and tune into KPIX to catch glimpses of the game. There she is, wearing giant earphones over her coiffed hairdo, clutching a microphone and greeting audiences when…

All of a sudden, the kitchen begins to sway ominously. On screen, Wendy’s entire body language turns to steel and with a grimace, she says what we are all thinking… “That was an earthquake.”

I turn to look at Maggie, who is seated at the kitchen table clutching a crayon. She cocks her head sideways as if she is listening to the sounds of the earth grinding, then turns and looks askance at me. The brass chandelier above the table rocks from side to side as I sweep her into my arms and carry her into the doorway, mindfully turning off the gas burners as I pass. Its just my luck that there is another adult was in the house— the girls’ dad is just downstairs in his home office, and now he is bounding up the stairway to assure his bewildered kid and I that we were all ok. I am grateful that he volunteers to venture out onto the streets to pick up his daughter Mikka, who assured us later that aside from suffering the effects of a room full of frightened children, she was perfectly fine. Even from across the room, I can register Wendy’s terror on the TV screen in the last seconds before Candlestick lost power and the station went black—a terror that was almost audible in my mind, so clearly did it cry out: “Where are my children?”

I don’t know why exactly but later that night, I decide that I must spend the night in my dorm room at Mills College, roughly nine miles away. After calling my mom minutes after the quake struck (and am lucky to get through since ten minutes later all lines are completely jammed with panicked calls), I borrow a car from the family and drive towards school. The streets are both eerily quiet and electric with danger. I turn off Grand Avenue onto the 580 freeway, climbing nervously up the onramp towards a stream of cars that in my imagination are fleeing the ruins of the city. In slow increments, rolling up above the dashboard is the fullest October moon I had ever seen, rising into the darkness, pale as ice, ruling the night.

For more 1989 tv amazement, check this out!