Leanna M. Dawydiak

My memories of the Loma Prieta quake are so vivid that it could have happened yesterday.

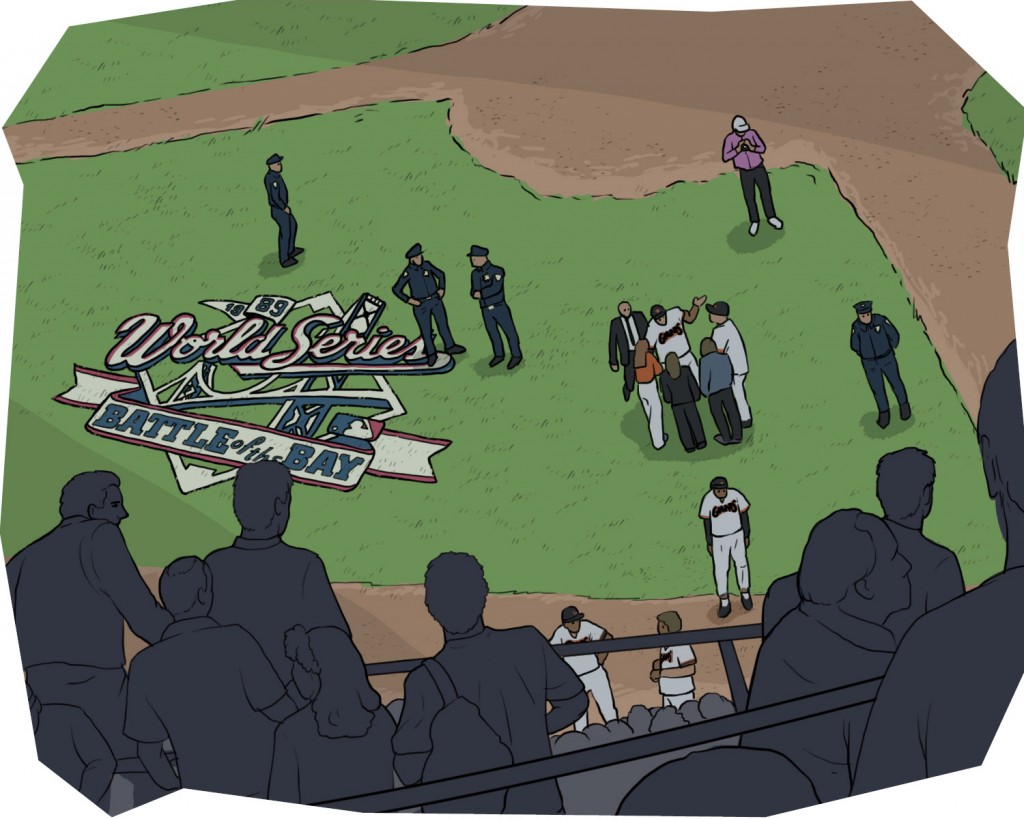

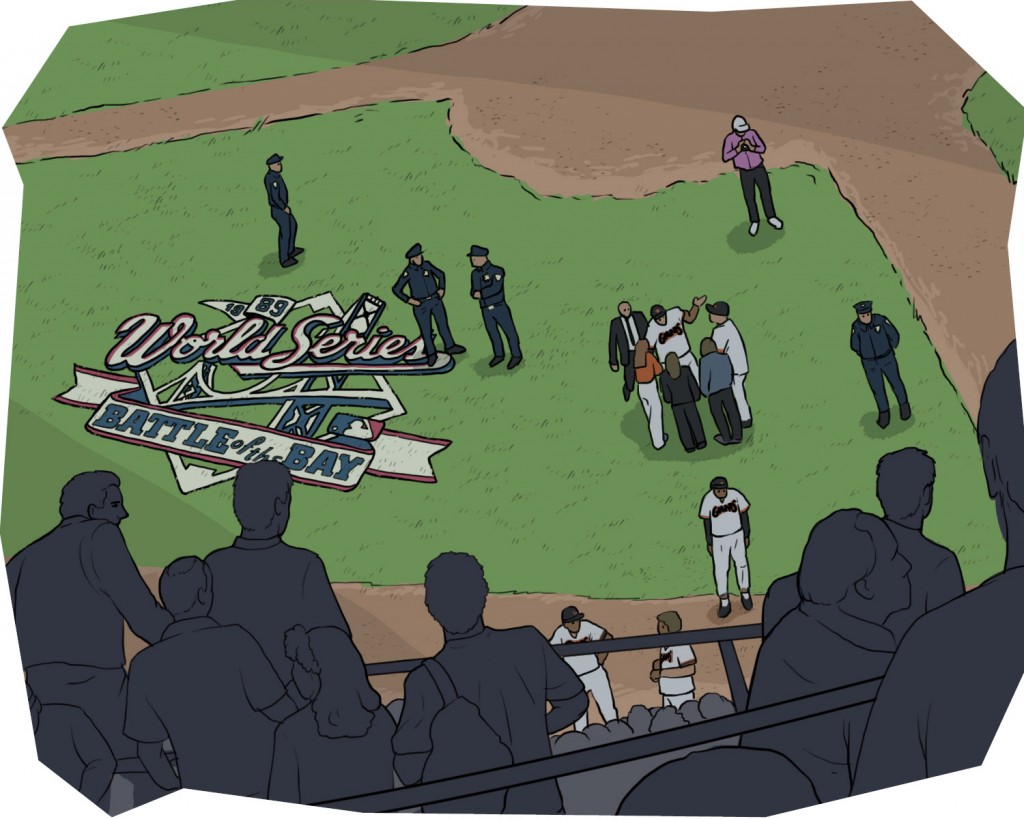

The day of the quake, I had been looking forward to going to World Series Game 3 at Candlestick Park. I had great seats because my husband, Reno Rapagnani, was the Chief of Security for the Mayor of San Francisco, Art Agnos, so I was going to get to sit with his staff just left of home plate along the third base line. I had driven out there with my father Gene Dawydiak, stepson Reno Jr. and my sister-in-law Diane: Gene and Reno Jr. were sitting in the upper deck but Diane was below with me. We had planned to meet back at the car after the game we were sure we were going to win. Reno was busy handling things for the Mayor and I had no idea where he was.

In any case, just before the game was to start, I was looking out towards the Sony Jumbotron and suddenly I felt like there was movement under my feet and the stadium seemed to move in a circular direction; a shift, if you will, and I think it was towards the right. I could actually SEE the movement. I can only describe it like Candlestick Park was a cup on a saucer and someone was twisting the cup on top of the saucer. Being a native San Franciscan, I knew we had just had an earthquake, but I didn’t worry too much as I had been through many in my life. I think it was the “neophytes” who alerted me that this was no regular earthquake so I got moving, trying to make my way up to where my dad was sitting.

When I got to my dad’s seats, he and my stepson were sitting there like nothing had happened. I told my dad, “We need to go, this was a bad one.” He said, “You’re overreacting… the game will start any minute.” All this, in spite of the fact that both teams and their families were all down on the field holding onto each other and not at all looking like they were ready to play baseball. I tried telling my dad, “Look, the Jumbotron isn’t even working…There’s no game, Pa.”

I finally got my dad to move by saying, “Let’s go down to the cop substation and see what’s up.” I was an officer in the SFPD and I knew my dad would come with me if I told him we were going to where the cops were. Sure enough, that did the trick and we found a quick route to the substation. On our way there, someone in front of us had a portable TV, which showed the Bay Bridge collapse and all the people that were trapped. After seeing that, we all knew that we had to get out of Candlestick Park in the event there were aftershocks that might bring the stadium down.

It seemed to take forever to get to our car, and then it was a very slow trek back to my parents’ house in the Richmond District. In fact, when it rains it pours, as they say, as my car started to overheat, which it never had done before. I had no idea where my husband was and worse, where my 2 year old daughter was: she was with her “surrogate” mother/babysitter, who lived on Webster Street near the Safeway in the Marina (where, as we found out later, took the worst of it).

When Reno finally got to our daughter, he couldn’t get “Mama Rosie” and Frank to leave because Frank was frantically looking all over the house for cash he had hidden all over the place (not unusual for old-fashioned Italians to do). I think my mother eventually got them out.

After dropping my father off at home, I knew I had to get to my house and make sure it was secure; this was on Museum way near the Randall Museum. Once I saw things were fine, I immediately suited up in my SFPD uniform and headed to the Hall of Justice as the call had gone out that any off-duty officer who could get into the City was to report ASAP.

I could write so much more about my duty on 6th and Stevenson…my “guarding” the Giants when they came to the Moscone Center to visit people who were homeless for the time being and getting to specifically “guard” my hero, Will Clark, who towered over me. I had to warn them that the people in the Moscone Center weren’t like the ones in the Marina, but that it was more like the inside of a prison with there being knife fights and the like.