Monica Espiritu

I had just turned 25. I was hanging out with my folks for an early dinner in front of the television in their little Union City house. Like most people in the Bay Area, we planned on watching the A’s and the Giants, just the three of us. Several people in their neighborhood pulled into their driveways around 4:30pm. My parents were already finished cooking dinner by the time I walked in the house.

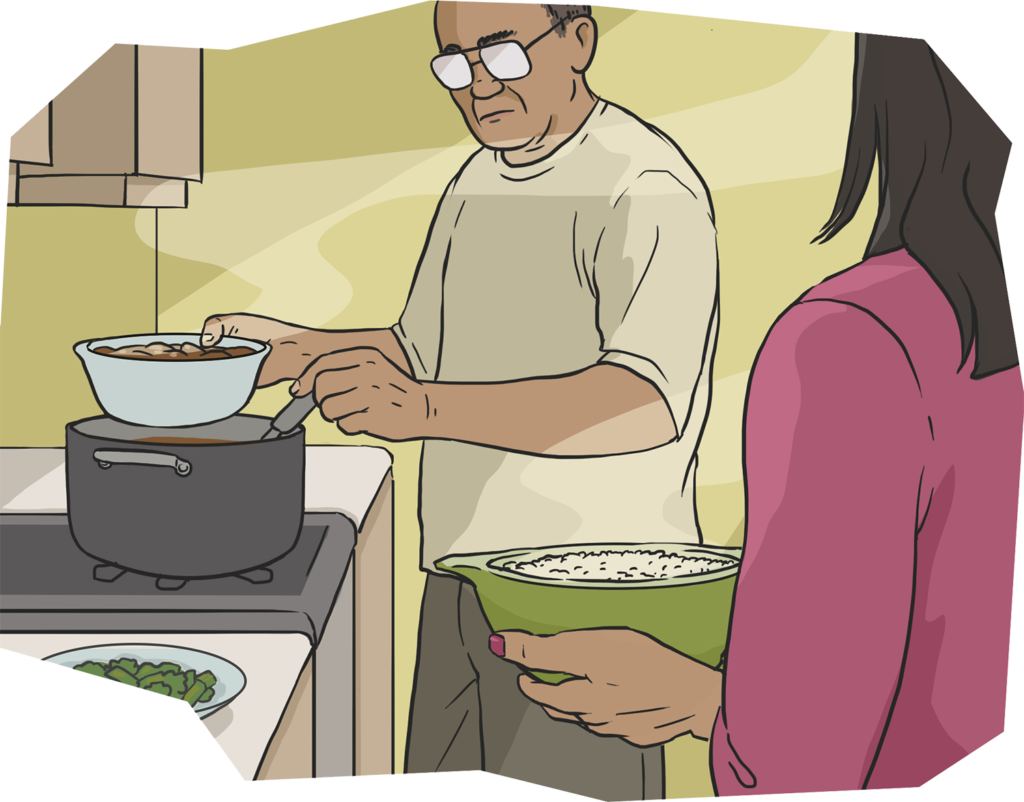

My dad and I were in the kitchen spooning rice, adobo and vegetables into bowls for the dinner table when suddenly a rumbling began.

My parents had experienced earthquakes in their youth in the Philippines. As a Bay Area kid, I’d gone through a handful of drills. In high school, I accused a kid in math class of kicking the back of my chair when in actuality we were in the midst of an earthquake, but I knew to jump under my desk when he said, “It wasn’t me!”

“Just another earthquake,” I thought in the nascent moments of the Loma Prieta.

I then found myself standing with my feet shoulder width apart, holding on to the counter and watching the lawn in the background roll in waves and my parents’ 25 foot mulberry tree sway. My dad set down the bowl he was carrying, kept his balance by holding onto the counter, and stared at the swaying tree. In my mind’s eye, the entire scene seemed to have moved in a weird suspended animation because I had enough time to glance in the other direction to the front yard through the living room’s picture window. I saw a couple of cars parked across the street ride asphalt waves. My mom was standing, slightly swaying, on our walkway watching the same scene.

After the rumbling and waves subsided, she came back in the house. My parents and I put the few books that tumbled off the family room shelves back in their usual places. We put all the food on the table. “Wow, that was a big one, ” my dad said nonchalantly. My mom and I agreed. We sat down to eat. My dad turned on the television as he had done hundreds of times in that house. We passed food and drinks back and forth to one another like another dinner we’d had together. Had we become desensitized to earthquakes?

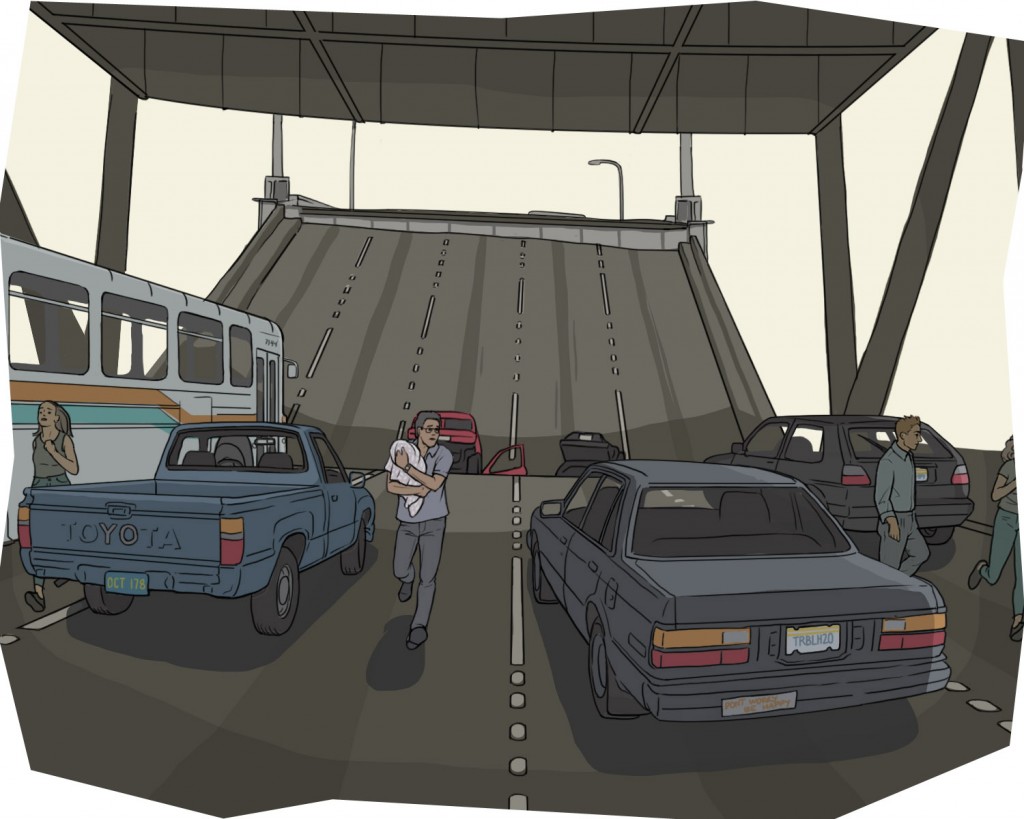

Then, the clanging of silverware on plates and chitchat ceased as the image of the Cypress structure, flattened and with clouds of dust and debris surrounding it flashed on the TV screen. It brought a pall to my parents’ home. The Cypress structure where our family had driven time and time again since we relocated to the Bay Area from Hawaii. The stretch of Highway 17 that we loved because when my mom or dad drove on it at 60 miles an hour, we undulated. With the Cypress Structure in our little VW Squareback and later our Chevy Nova and VW Van. We used to ride the waves on that stretch of Highway 17 in our cars. It was suddenly gone and I felt my heart flattened along with it.