Kirsten Casey

I was raised in California, so I am no stranger to earthquakes. The week of eighth grade graduation, we had a 5.8 earthquake. During my braces removal, I ran out of the orthodontist’s second floor office. Standing on the balcony, watching the Salinas Valley sway, with a full dental dam in my mouth, I was not cool. But the earthquake didn’t scare me.

When I was twenty-two, beginning to teach at a school just behind Santa Clara University, the Loma Prieta earthquake struck the Bay Area. Sitting at my desk, grading papers, I heard it first. That unmistakable earthquake rumble. A handyman working in my room turned to me. It kept going. He said, “We need to get out.” We ran onto the parking lot at the center of campus. The daycare kids poured out too, screaming. The earth was a rolling, liquid force. When it ended, I was unaware how devastating that rolling had been. This was before cell phones. I called my fiancé, Mark, from school, and he told me that he was talking to a Palo Alto client who asked, “Can you feel this? We are having an earthquake.” Then the line went dead, and then he felt it.

We spent the afternoon trying to track down Mark’s sister, Julie, who moved in as my roommate, that day. She left a note on the kitchen table in our Los Gatos apartment saying she was heading to San Francisco and she would see me later on. Did I mention we didn’t have cell phones? She befriended a couple in a hotel lobby who actually knew her grandparents in Oregon, but all of the phone lines were dead.

Mark’s grandmother lived a block from the school, so we met there. During dinner, Mark’s uncle insisted that Julie’s photo was the only one swinging in the hallway photo gallery (this meant she was dead.) Julie was finally able to reach us by payphone (does the next generation know what this is?). Although relieved, we slept restlessly, awakened by several aftershocks. This earthquake scared me.

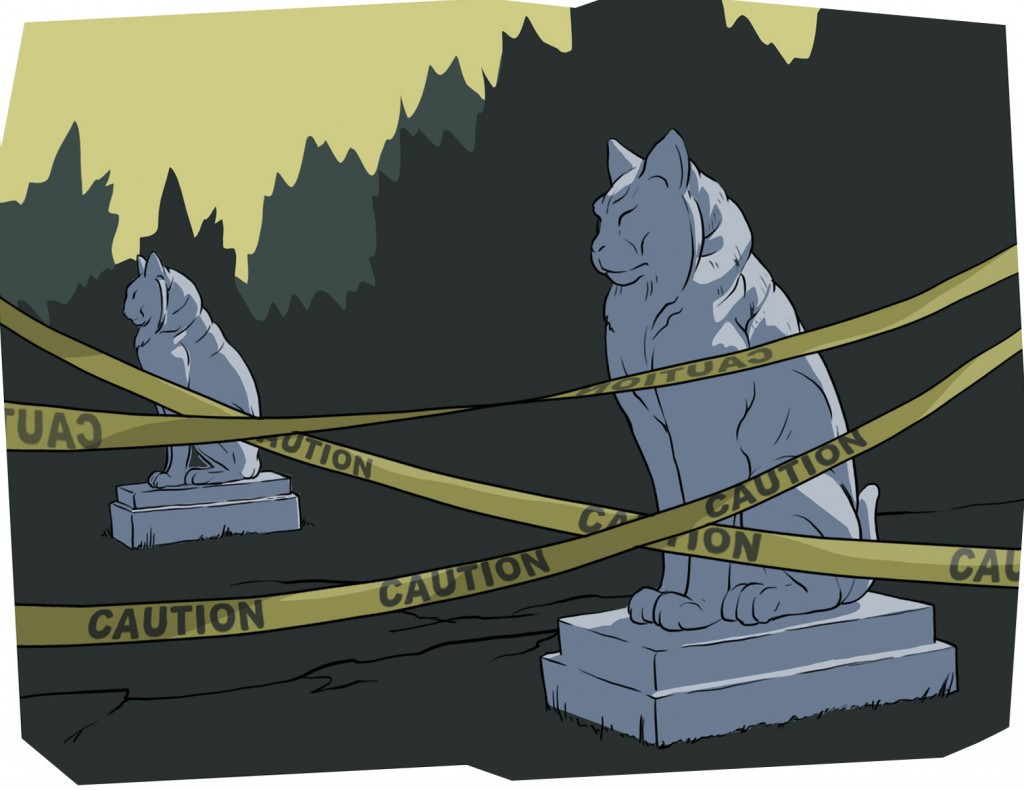

Road closures prevented me from returning to our apartment until the next morning, since we lived in Los Gatos, the epicenter. Entering the apartment was eerie. Every frame was at a severe angle to the left, and every cabinet was open. Pushed from the wall, the refrigerator doors were open, with contents spilled on the linoleum. Our new TV was face down across the room, and worst of all, the toilet was full of potpourri.

When Julie arrived home that morning, we cleaned, picked up glass, straightened frames, and ran out of the door anytime we felt a slight shift. In the afternoon, we walked out to assess the damage in town, and were stopped by a police officer asking if we were residents. I am not proud of what I did. (Call it earthquake hysteria.)

I am a rule follower, not a rebel. Yet, I lied to a cop. I made up an address in a restricted area of town, and he was really, really pissed. I don’t know what possessed me to do this. My future sister in law looked at me with shock, horror, and a little admiration. Before the Internet, and the constant stream of information, before everything could be answered by looking at a screen, we had to go out into the world and lie to cops. I lied because I loved that town, and I wanted to see what needed fixing. I lied because of morbid curiosity. I lied because this was the first time I understood that some things are beyond our control, especially when they have to do with fault lines.