Jamie Batt

I was on the bus heading home after a day of school at Los Gatos High…we were about halfway up Hwy 17 when I noticed that something was amiss. I gazed out the bus window with a growing sense of confusion: the trees on the hillside to the right of the bus were swaying wildly- I couldn’t remember any wind that day, I looked out the left window and the confusion turned to awe and fright very quickly.

The cars on the other side of the road were rolling, and the center divide was cracking before my eyes. This is when I realized that the motion of the bus was not at all normal. The other kids on the bus were exclaiming and moving chaotically from one window to the next trying to figure out what was going on…the bus driver had stopped the bus but it was still moving, she kept telling us to stay calm and that everything would be OK.

Once the rolling stopped- the bus driver decided that she had to get us all to our bus stops and safely home…so up we went. The hardest area to traverse was on Summit Road where a giant fissure had opened up- but that bus driver was able to maneuver us safely around it and to the last stop.

When I made it home, everything in the house was on the floor: the wooden legs of my bed had scratched circles into the wood floor from the motion of the quake. I will never forget how out of control everything felt- or how small and insignificant I felt…nature at its scariest.

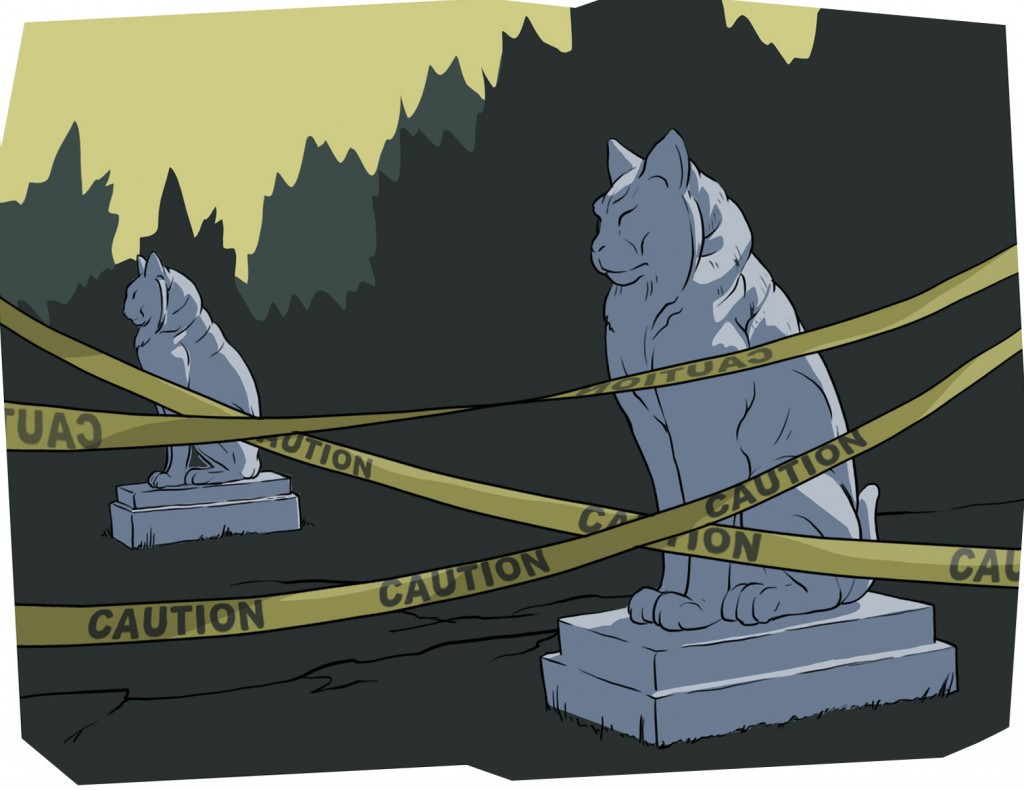

Downtown Santa Cruz was never the same after the quake. Some of my favorite old buildings were now blocks of rubble behind chain link fences…the buildings that eventually went up to take their place have no soul- no sense of history and time…I walk down the Pacific Garden Mall now, I don’t think it is even called that any more, and see everything that is missing…shadows of the past, and I feel an overwhelming sense of not right-ness.

I don’t visit Santa Cruz much any more. It just isn’t the same.