Dorothy Santos

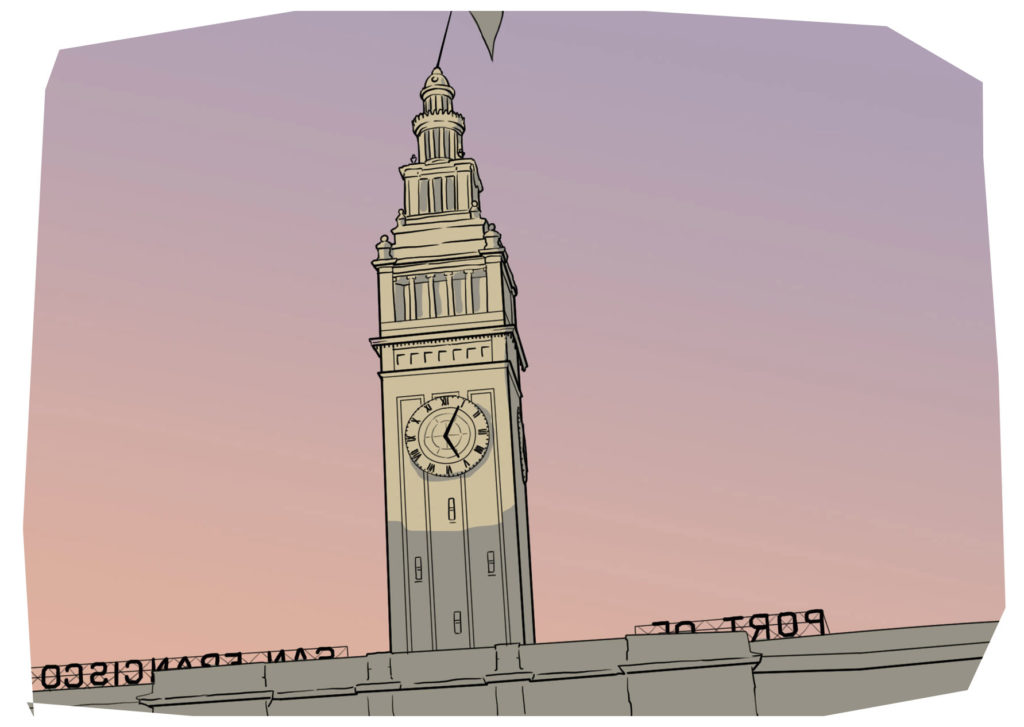

It was a normal day at school and friends greeted me happy birthday. My friend Wendy, her cousin Cherry, and I were waiting patiently for my Dad to pick us up and take us back to our house. He dropped us off and left quickly to pick up my Mom from work. At the time, she worked in downtown San Francisco. Dad mentioned coming home right away in the hopes of setting our minds at ease that we would be okay. Naturally, he instructed us to not cook anything for fear of burning down the house and not to open the door to strangers.

Although it was my birthday, we didn’t have anything special planned for the evening. Wendy’s parents were going to pick her and Cherry up later on in the evening. They were more than happy to stay for a casual birthday dinner with me, my parents, and grandparents. It was a no frills kind of night and I didn’t particularly like the idea of going out for dinner since I loved my grandpa’s pancit and a birthday cake from one of my favorite bakeries in the Mission, Dianda’s.

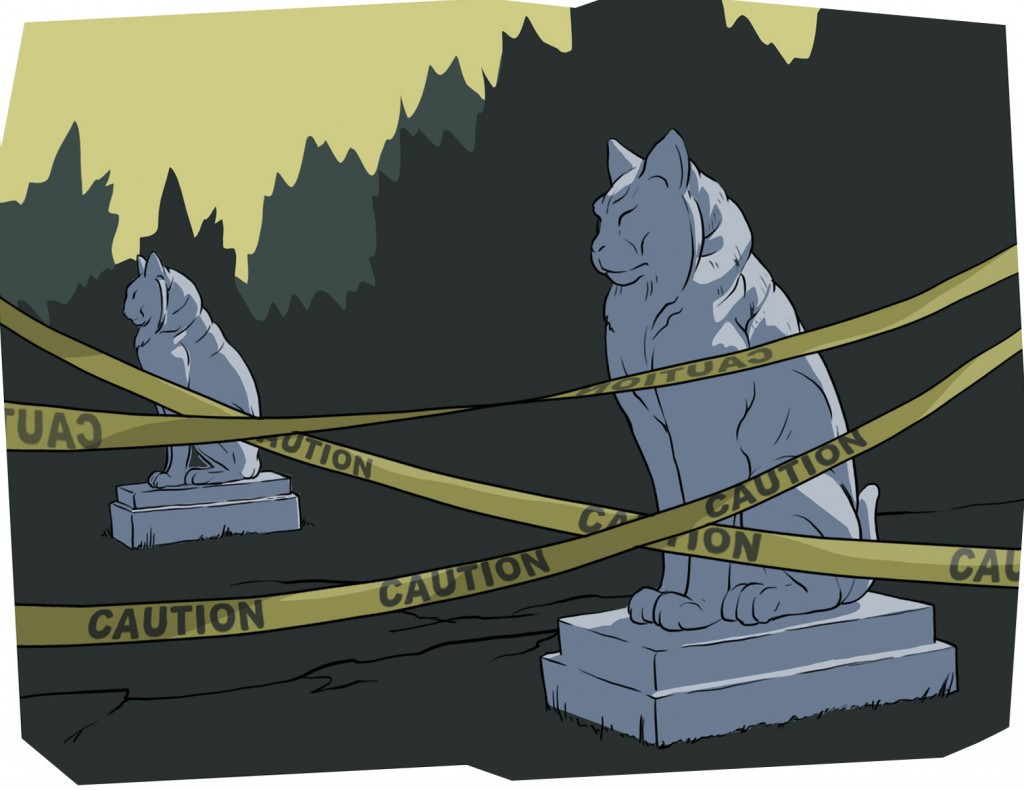

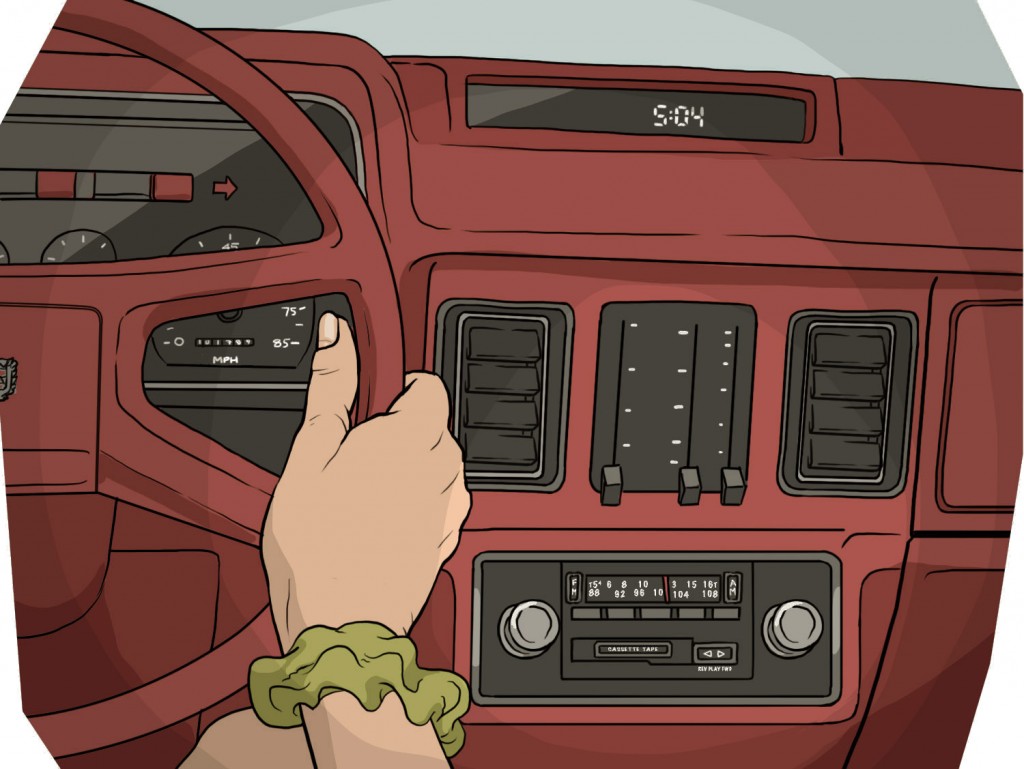

Wendy, Cherry, and I waited patiently. Since the San Francisco Giants were playing in the World Series, we decided to watch the game. It started to rumble. I could see the house and whatever was in view looked as it were being plucked like a flower from the ground. Before the Big One, I never felt an earthquake of that magnitude. I felt small ones. Those little quakes made me think of the Jolly Green Giant moving around softly in his sleep. It would cause a minor shake, but nothing too terrifying or worrisome. This particular night was different. The land was angry and moved the same way my mother shook me when she was furious with my sharp tongue. It lasted relatively long and the mahogany chair was far too heavy to move away from the desk. We panicked. Then it stopped. Our eyes were big and we looked at each other. Cherry mentioned feeling similar earthquakes in the Philippines. It was good to know she wasn’t too terribly shaken (no pun intended).

But we lost power. We couldn’t communicate with anyone and had to wait patiently. We sat on the stairs looking outside to keep on the lookout for any of our family members. An hour of waiting felt incredibly long and the anxiety of wondering where our parents were after the earthquake drove us to the darker and morbid parts of our imaginations. We cried. Finally, my grandfather came home. He wasn’t the most communicative man. His silence and settling in after a long day of cleaning after students at Cogswell College was comforting somehow. My parents got home after my grandpa’s arrival. Wendy’s parents came shortly after them. They left straight away, understandably.

My grandpa was chopping and cooking. Despite the gas range working, we didn’t have electricity. In hindsight, my grandfather probably shouldn’t have cooked. Then again, nothing ever stopped him from doing what he wanted to do. It was still daylight so he cooked with a bit more urgency than usual. By the evening, we gathered up all the candles my mom and grandmother collected that were reserved for burning on Sundays in religious observance. It was a candlelight birthday dinner listening to the small magenta colored transistor radio my father bought me from Radio Shack. It came in particularly handy that evening.

Home Alone

My 12th birthday was one of the most memorable ones. But 2 years later, the Oakland fires happened during my 14th birthday party. I started to have a complex of starting natural disasters. So much of the movie Amelie resonated with me when I thought back to my childhood. But I grew up and realized there were no correlations, just coincidences. I remember wishing for no school the following day. No such luck.

Specific place: Bayview District (apparently, my parent’s place has the strongest, stable rock in San Francisco)

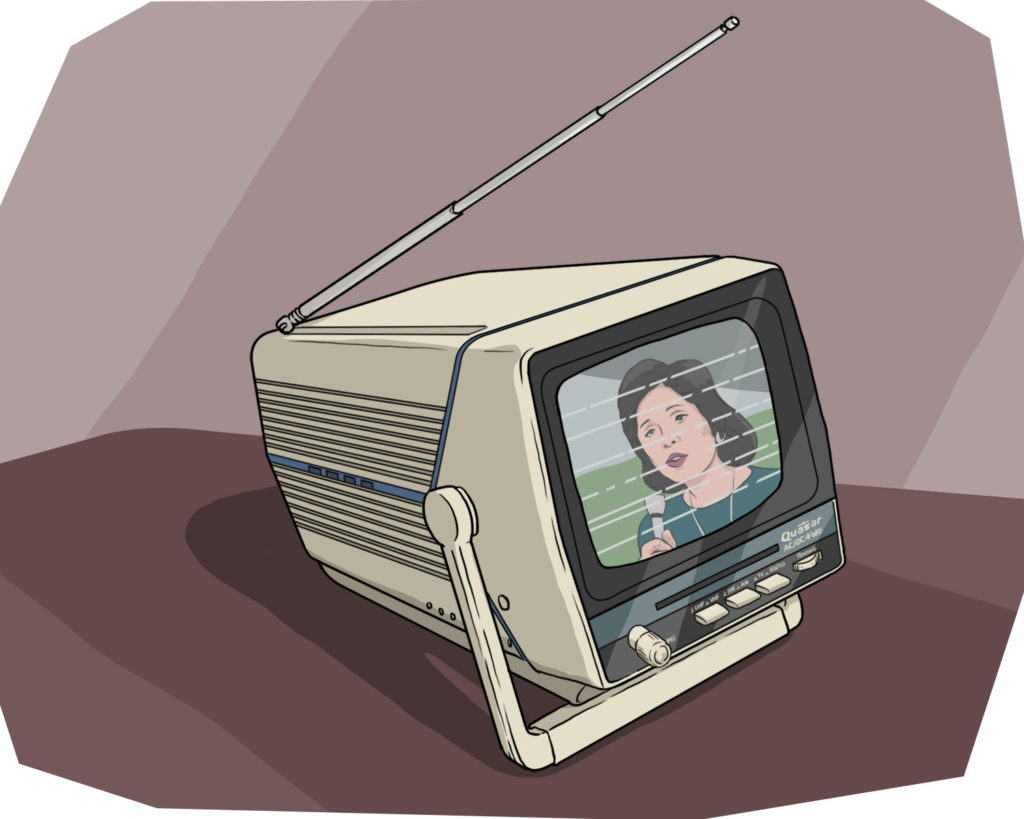

Thoughts, emotions, or associations: Watching the news and seeing the destruction across the city. Houses in the Marina District were uprooted from their foundation. The worst sight of all the images mediated through the TV screen – the split Bay Bridge. The lone car that plunged into the split made made it difficult for me to go over the Bay Bridge without panicking, for years.